This article is part of my MRI series. See Nuclear this Magnetic that - MRI series.

All the scary labels outside the scan room, the chill, and the rhythmic humming and chirping inside—it’s enough to make anyone wonder: What on earth is my body about to go through? Will I see aliens? Seriously, how harmful is this?

No concerns for radiation damage

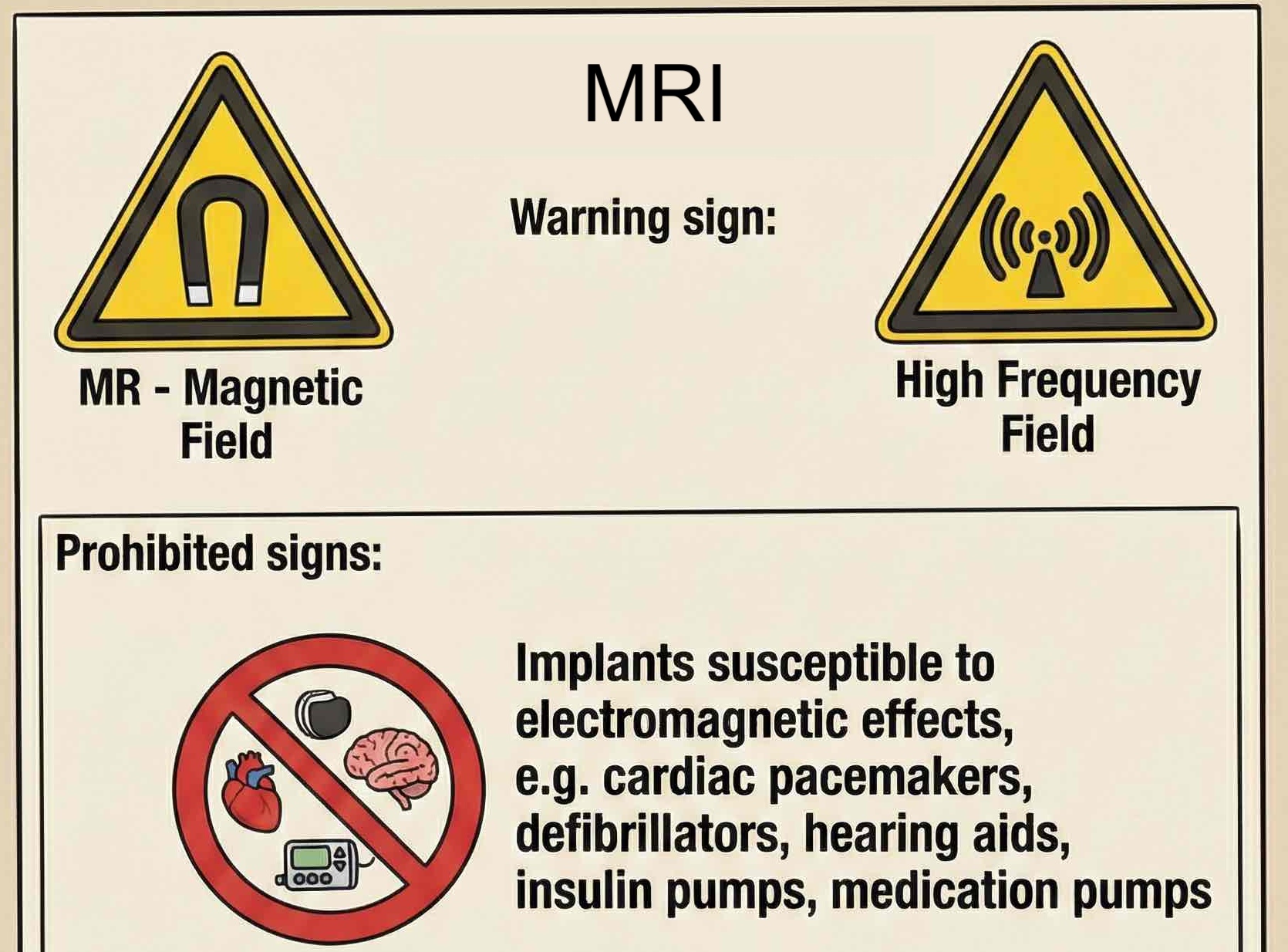

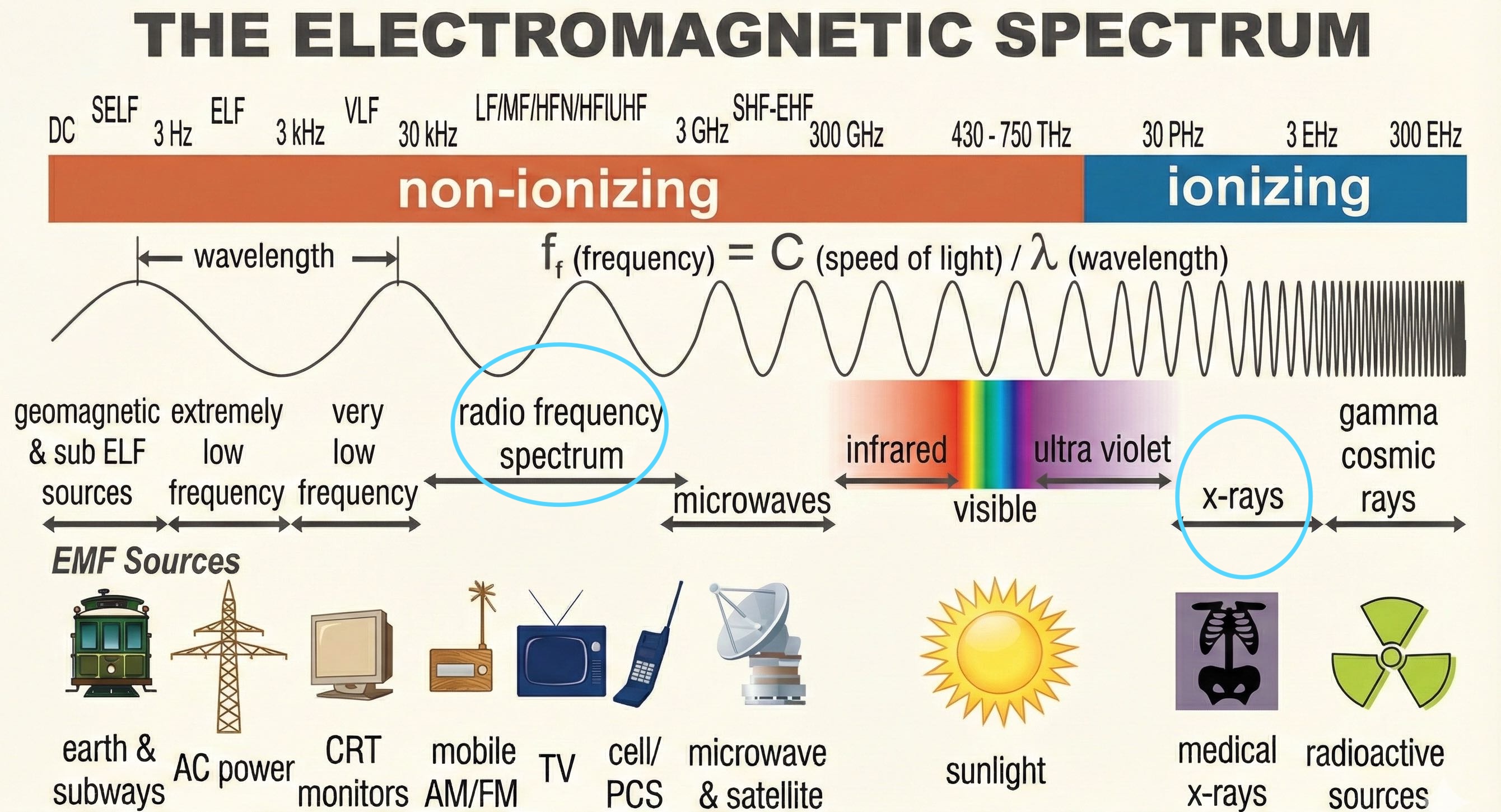

The fear of “scan-related harm”—specifically radiation damage—usually stems from X-rays and CT scans. Those use ionising radiation, which carries enough energy to directly damage the DNA in your cells, potentially increasing cancer risks over time.

Over years of development, ionising radiation dosages have been optimised to the absolute minimum, meaning the risk is incredibly small. If a doctor prescribes a scan, you shouldn’t give it a second thought; the diagnostic benefit far outweighs the tiny potential risk. (On the other hand, if you’re just “super keen” to stay on top of your health by booking a full-body CT every few months without symptoms… please don’t.)

Now back to MRI…

The radiation used in MRI consists of radiofrequency (RF) waves. These are in a similar range to FM radio and walkie-talkies. They are non-ionising and much lower in energy. The strongest human scanners currently in existence use a 500MHz frequency, while common hospital machines sit around 100MHz. These waves simply aren’t powerful enough to cause molecular damage. For comparison, most modern WiFi operates at 5GHz (5,000MHz).

Heating things up?

Microwaves is also an RF (typically using around 2.4GHz), but obviously it can cook some meat pretty quickly. Hmm, not sure if being cooked is any better than a mere risk of cancer?

Luckily, physics makes that scenario nearly impossible in a scanner. Frequency is the first factor; 2.4GHz is orders of magnitude more effective at heating water molecules than 100MHz. Then, there’s the power. A microwave oven uses 800W to heat a few hundred grams of soup; an MRI on “full blast” doesn’t sustainedly deliver much more than 20W, and that’s distributed over the tens of kilograms of your entire body.

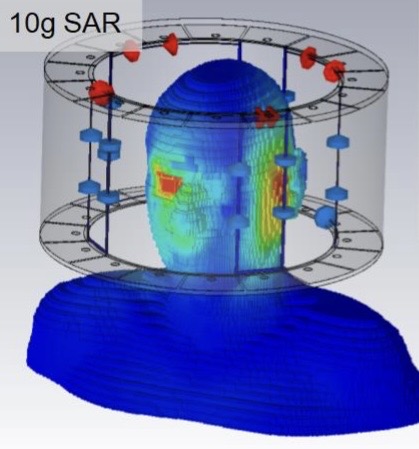

In fact, heating is the core safety focus in the MRI world. By law, RF coils must pass so many layers of safety validation that it can actually be quite limiting in high-field MRI research (it nearly ruined my PhD! 😂). We don’t just look at overall power; we perform detailed modelling and experiments to map exactly how heat is distributed in the body to make sure it’s safe.

We use electromagnetic models to simulate the RF waves coming off the coil, then apply realistic human tissue models—accounting for different genders, ages, and BMIs—to calculate the heat generated at every location. The worst-case scenario is then compared against legal limits for heat absorption (e.g., for experimental head scans, no more than \(20\text{W/kg}\) in any \(10\text{g}\) of tissue averaged over 6 minutes). These limits are based on conservative models designed to ensure body temperature remains safe.

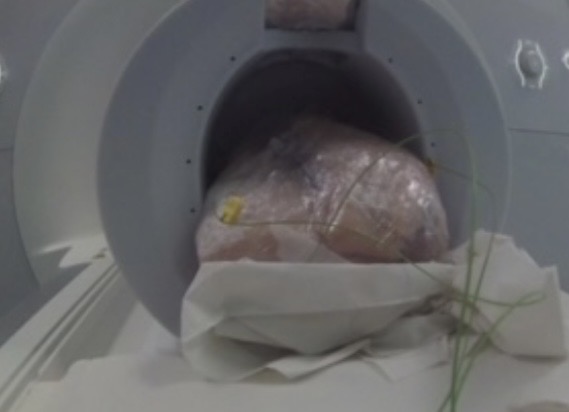

And yes, this rocket science doesn’t get signed off until we’ve put a few pieces of pork shoulder in the scanner to physically record the temperature change…

But the magnet is really strong

A standard hospital MRI uses a 1.5T or 3T superconducting magnet, which is about 1,000 times stronger than a fridge magnet.

Fortunately, even at this strength, there is no evidence of lasting effects on the human body. Some people feel a bit dizzy when moving in or out of the scanner (due to the magnetic field interacting with the inner ear), but that goes away quickly once stationary.

Researchers have even studied mice in much stronger fields for longer periods.1 They concluded that long-term exposure to 10.5T and short-term exposure up to 16.4T caused no lasting health effects. I doubt we will see full-body human scanners that strong for at least another few decades.

Summary

However intimidating the technology may sound, the core mechanism of an MRI is not harmful to your health:

- It does not involve any damaging radiation at all - in a sense ‘safer’ than X-ray.

- The magnetic field, while strong, has no lasting effect on body.

That said, there are more mundane aspects of the scan that can be genuinely dangerous if ignored. We’ll dive into those in the next article.

doi: 10.1002/mrm.28799↩︎